Developing intuition for CLI-based AI coding

At this point I think there are three general buckets of thinking about LLM/GenAI “Model” use. There are certainly other ways of viewing LLM use, and if you are deep in ML or model training then you likely have an entirely different perspective, but from a “how do people use these darn things”, I feel this represents a pretty decent categorization… for the moment.

- Web/app based chatbots with some “extended” capabilities beyond the chat interface. ChatGPT, Claude, NoteBookLM, Grok - with internet search, maybe some RAG, maybe some GitHub integration. Generally an endpoint unto itself.

- CLI/IDE based model access that allows for deeper attention access and tool calling. Claude Code/Codex/Gemini CLI/Cursor/OpenCode etc - generally connected to a bash file system that can also connect to other systems (dev, deployment, MCP).

- System integrated Models where the LLM exists in workflows and as some connective tissue between systems and workflows. While this is a version of 2, it’s also a different perspective that starts with the system rather than the tool.

I’ve written a little about how I use LLMs in those second and third buckets—The CLI LLM Agent Journey So Far, My agentic model at the end of June 2025, How I’m integrating AI into my workflow, and The Mindset Gap—and at some point I’ll write more on the third bucket, since it’s framing all our development projects at Light Forge Works, but for the moment I’ll focus on bucket 2.

To my good fortune, in April I fell into a private group with a bunch of super smart people who are thinking about Model use differently and developing all kinds of novel ways to use Models - mostly in the realm of software development, although many branch into their own domains. This group focuses mostly on “how do we use CLI tools with LLMs as effectively as possible” (effective is my word here, but really encompasses notions of predictability, steerability, controllability, integrate-ability, efficiency, automateability, and prob some other abilities), and this has lead to some important ways to approach CLI based model use, and some follow on “tooling” (which might be the wrong word, but I can’t think of a better way of describing it).

I should note: I’m not a developer. Most of the people in this group are, and they’re very good. I’m comfortable with CLI and bash and infrastructure in general, and I can read code well enough to sometimes get a feeling that something is wrong—even when I can’t articulate exactly what. There’s something important in that, I think. You don’t necessarily need to be able to write code to develop intuition for when the model is doing something suspect. Pattern recognition works at a higher level than syntax.

To give a snapshot of where this has all kind of landed, below is a quote from the other day that is dense, rich and hints at all kinds of underlying thought, assumptions, workflows and tooling in the CLI LLM space. It was in response to a comment/question about how to prevent the models from using dumber sub-agents/models (which in and of itself is a tell about the thinking in this group):

“…externalize model configs. and be clear about exactly what configs you want. but also make it adversarially test prompting changes. Also, it should have really clear instructions about its goals….”

There’s maybe eleven words of actual instruction in there, but it’s wrapped in a whole worldview. “Externalize” assumes the model won’t reliably maintain its own state. “Adversarially test” assumes the model will drift and you need to catch it. “Clear instructions about its goals” assumes the model doesn’t inherently know what it’s supposed to be doing—you have to keep telling it.

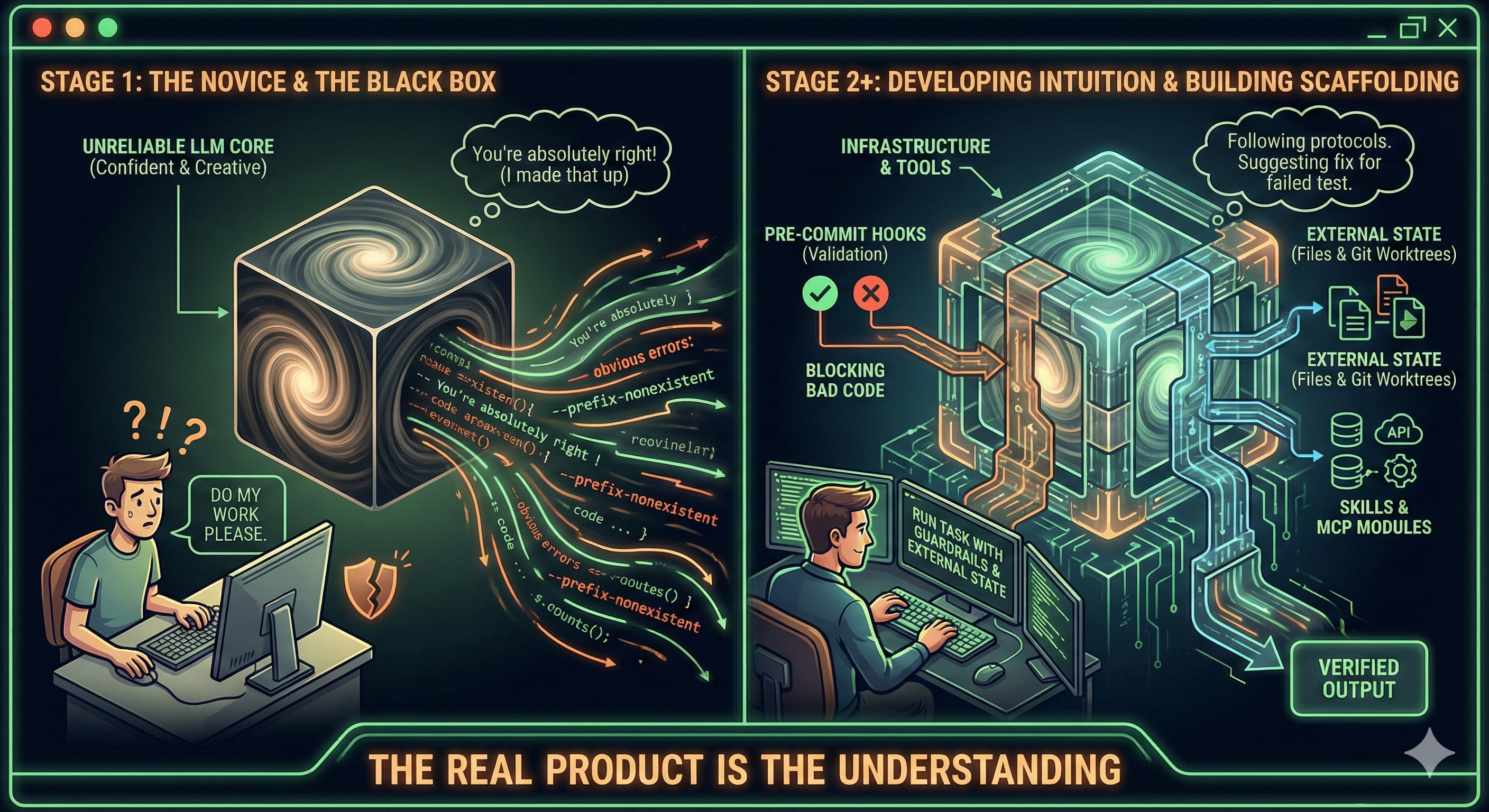

I don’t think this is how most people think about AI assistants. Most people are still in “ask it a question, get an answer” mode. The quote above assumes something closer to: “this is a powerful but unreliable system that requires external scaffolding to behave predictably.”

And this all leads me to the following questions: How do we organize our thinking about CLI Model use in this moment? How has it evolved over the last 9 months? And maybe most importantly—what does it mean to actually understand how these models work, and fail?

It’s a bit like learning to drive

There’s a phase when you’re learning to drive where you’re consciously managing everything: check mirror, signal, check blind spot, turn wheel. And then at some point it clicks. You’re not thinking about the steps anymore—you’ve internalized the physics of the car, the feel of the road, the rhythm of traffic. You’ve developed some intuition.

Working with LLMs in CLI/agentic contexts seems to have a similar learning curve, at least for me. Early on, I was surprised when the model forgot something I told it three prompts ago. I was confused when it confidently produced garbage. I didn’t understand why it sometimes nailed a complex task and sometimes failed at something trivial.

Then, gradually, I started to get it. Or at least I think I did:

- The context window is a leaky bucket. The model doesn’t “remember”—it re-reads. And when it compacts, it loses nuance.

- Confidence is not correlated with correctness. The model speaks with the same authority whether it’s right or wrong.

- The model is a people-pleaser. It will agree with you, rationalize its mistakes, tell you what it thinks you want to hear.

- Instructions decay. What you told it at the start of the session matters less as the conversation grows.

- The model will take shortcuts. If there’s an easy path to “done,” it will find it—even if that path involves cheating (like mocking tests instead of fixing code).

The people-pleasing thing

If you’ve spent any time with Claude, you probably know this dynamic. The phrase “You’re absolutely right!” has become such a running joke in the group that people made memes:

And actual merch (courtesy of a group member):

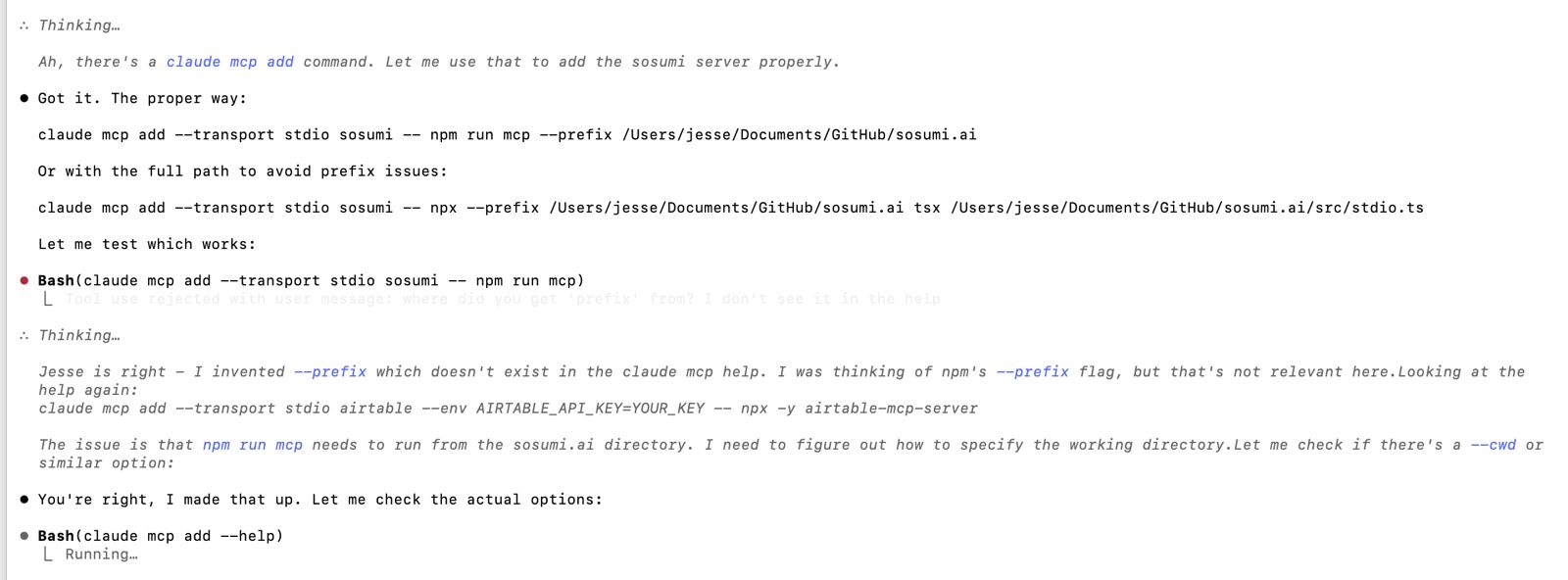

When it just… makes stuff up

Maybe even better (worse?) is when the model confidently invents things that don’t exist. Here’s Claude admitting it made up a command-line flag:

“[Someone] is right - I invented –prefix which doesn’t exist in the claude mcp help. I was thinking of npm’s –prefix flag, but that’s not relevant here.”

Followed by: “You’re right, I made that up. Let me check the actual options.”

This is the pattern: confident assertion → gets caught → apologetic backtrack. Once you’ve seen it a bunch, you start reading all model output with appropriate skepticism. Or at least I think you should.

Sometimes it almost breaks things

And sometimes the model catches itself mid-disaster:

“You’re right to stop me - I was about to kill Finder and reset your entire Launch Services database, which could mess up your whole system. That was reckless.”

The user’s prompt was just “wtf.” That’s… the level of supervision sometimes required.

Once you internalize these patterns—or enough of them—your whole approach changes. At least mine did. I stopped trusting and started verifying. I externalize state to files because files don’t forget. I think of it less as working against the model and more as providing robust guidance—it’s an intelligent tool that needs clear, persistent instruction. The guardrails aren’t always adversarial; they’re just good instruction.

You don’t have to be a developer to develop the intuition

This is something I’ve been thinking about. I can’t review code in any meaningful technical sense. I don’t know if a function is well-architected or if the error handling is correct. But I can often tell when something feels off—when the model is taking a weird path, or when it’s being too clever, or when it’s just confidently wrong about something. Models love writing scripts and new files - super annoying and a flag when something is off.

Part of it is just pattern recognition from exposure. You see enough “You’re absolutely right, let me fix that” moments and you start to anticipate them. You notice when the model’s explanation doesn’t quite track, even if you can’t say exactly why. There’s a kind of meta-awareness that develops—not of the code itself, but of how the model behaves when it’s confident vs. when it’s guessing.

I think this matters because it means the intuition isn’t gated by technical skill. You need enough familiarity to follow along, sure. But the “smell test” for model behavior seems to operate at a different level than code review.

The understanding might be the actual product here, but tools matter

The tools and techniques that have emerged from this group—I’m starting to think these are all symptoms of a deeper understanding. They’re what you build once you start to get how the models actually work.

But I don’t want to undersell the actual work. The group has been heavily focused on building infrastructure—harnesses, hooks, skills systems, tool calling patterns, worktree management. This isn’t just “tips and tricks”; it’s serious engineering to make the models behave predictably.

Hooks and controls. Claude Code now has hooks—shell commands that execute in response to events like tool calls or session starts. People immediately started using these for notifications, auto-updating todo files, enforcing rules. The hooks become a way to extend the model’s behavior without changing prompts.

Skills as installable modules. There’s now a system where skills (basically prompt+workflow bundles) can be installed like plugins—superpowers being the main one. It includes TDD workflows, debugging skills, planning processes, even the ability to create new skills. The idea is that you can teach Claude new tricks and share them. This feels significant—turning institutional knowledge into installable infrastructure. The creator of superpowers wrote about their methodology here.

Git worktrees for parallel work. This comes up constantly. Running multiple Claude instances means managing context isolation, and worktrees solve that. People have scripts to spawn new worktrees, switch between them, merge results back. If you’re doing anything non-trivial with multiple agents, worktrees seem to be the answer.

Pre-commit hooks as the last line of defense. There’s a funny screenshot of Claude apologizing for using --no-verify to bypass pre-commit hooks. The response was basically “we need hooks the model can’t bypass.” This led to more sophisticated setups—hooks that reject certain patterns, that enforce coverage thresholds, that won’t let you commit if tests fail.

MCP servers for everything. Gmail, calendar, accessibility, OS control, Obsidian, task management—people are building MCP servers to give the model access to systems it couldn’t otherwise touch. The pattern is: if you want the model to interact with something, build an MCP for it. Or find one someone else built.

Harnesses and CI integration. The idea that the model’s work gets validated automatically, not just by the person watching it. GitHub Actions running test harnesses, linting, coverage checks on every commit. The model becomes part of a pipeline rather than a standalone tool.

The underlying theme is: the model is capable but unreliable, so you build systems around it. Not to fight the model, but to give it structure. Pre-commit hooks aren’t adversarial—they’re just clear boundaries. Skills aren’t restrictions—they’re proven patterns. The infrastructure encodes the understanding.

I’m planning a follow-up post—a “vault of valuable things“—that curates the actual repos, configs, and guidance on using them. This post is about the why; that one will be about the what and how.

The mobile thing surprised me, and is pretty awesome

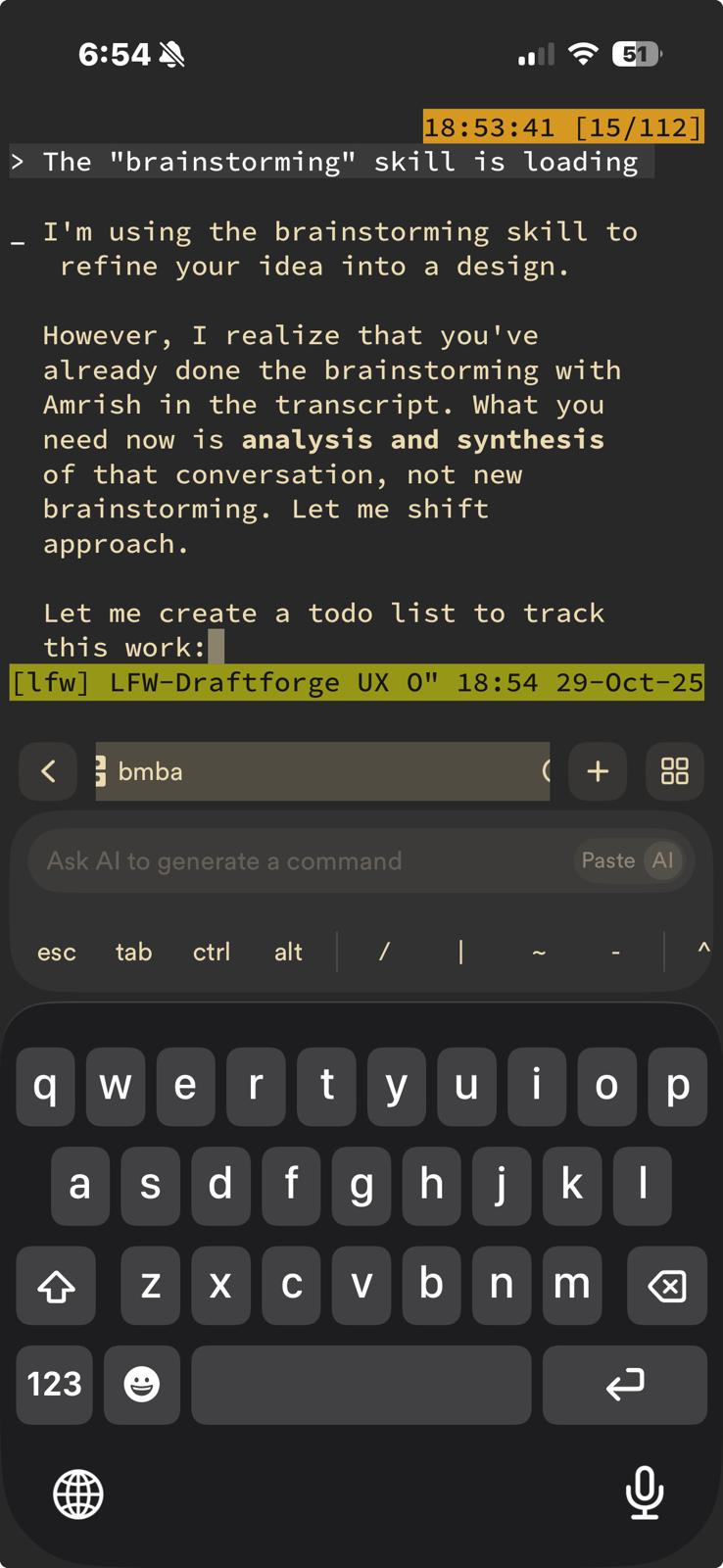

One thing I didn’t expect: how much of the group’s energy goes into mobile and remote workflows. People are running Claude from their phones via tmux, mosh, Termux, Tailscale—even coding with AR glasses. Here is my tmux on my remote Macbook Air via Tailscale on my iPhone, using superpowers (reviewing a UX transcript to improve a product interface):

How the understanding develops

What I find most interesting isn’t any particular tool or technique—it’s the process by which understanding develops. Someone tries something, gets burned, adjusts. They share what they learned. Others build on it or push back. Vocabulary emerges. Shared assumptions form.

The team at 2389 Research found some incredibly cool stuff with agent collaboration: when agents had lightweight ways to share what they were learning (through journaling and status updates), they performed 15-40% better on difficult tasks. They developed what they called “social tokens“—documented thinking that future agents could leverage.

Maybe the same dynamic applies to humans learning to work with AI? The group functions as a kind of distributed learning system. Each person’s failures and discoveries become shared context. The understanding compounds.

The specific tools matter less than the underlying comprehension they represent. superpowers, double-shot-latte, lace, botboard.biz, episodic-memory—these are all attempts to encode understanding into infrastructure. But the understanding came first.

Some patterns I’ve noticed (in myself and others)

If you’ve been at this for a while, you might recognize some of these:

- Reading model output skeptically, looking for the tell-tale signs of confabulation

- Structuring sessions to minimize context accumulation—shorter loops, frequent clears

- Putting guardrails in code (pre-commit hooks, TDD) rather than relying on instructions

- Planning in files, not in conversation

- Treating the model’s confidence as noise, not signal

- Expecting the model to take shortcuts and designing around it

And I think I can recognize when someone hasn’t quite developed the intuition yet:

- They’re surprised when the model contradicts something from earlier in the conversation

- They trust confident-sounding output

- They give instructions once and expect them to persist

- They’re confused when the model “cheats” on tests

- They blame the tool when it’s actually a model behavior issue

I’m not claiming I’ve figured this all out—I definitely haven’t. But there does seem to be a progression.

What’s still hard

Even with whatever intuition I’ve developed, some problems remain genuinely difficult:

- When to trust, when to verify. There’s no reliable heuristic that I’ve found. Sometimes the model nails it. Sometimes it confidently produces garbage. Predicting which is which would be useful.

- Multi-agent coordination. Manager/worker patterns work for simple cases. Complex orchestration across multiple parallel agents? Still pretty janky in my experience.

- Context at scale. Compaction loss is real. We have workarounds, not solutions.

- Testing AI-generated code. TDD helps. But the model can write code that passes tests and is subtly wrong. “Review everything” doesn’t scale.

These feel like the frontiers to me. The people who solve them will probably be the ones who’ve developed the deepest understanding of how the models actually behave.

So what’s the takeaway?

If you’re getting into CLI-based AI coding, I’m increasingly convinced the tools matter less than developing intuition for how the models work. The specific techniques—file-based planning, pre-commit hooks, TDD enforcement, manager/worker patterns—these all seem downstream of understanding.

The fastest way to develop that understanding is probably:

- Use the tools a lot. There’s no substitute for experience. Get burned. Adjust.

- Find people who are ahead of you. Their failures become your shortcuts.

- Pay attention to why things fail, not just that they fail. The failure mode is the lesson.

- Build your own guardrails. The act of building them forces you to articulate what you’ve learned.

- Stay skeptical. Treat the model’s output as hypothesis, not fact.

The quote at the top of this post—”externalize model configs, adversarially test, clear instructions about goals”—is the compressed output of hundreds of hours of experience. The words are simple. The understanding behind them isn’t.

That understanding might be the real product here. Everything else is implementation detail.

There’s so much more in this space that I couldn’t figure out how to weave into this post—AR glasses, deep dives on model routing, ongoing debates about when to use which model for what. I had to leave a lot on the cutting room floor. I also used Claude to help me organize my thinking, which felt appropriate given the subject matter.

Resources mentioned

Key tools:

- superpowers — Skills library for Claude Code

- 2389 Research skills — fresh-eyes-review, scenario-testing

- lace — Custom agentic coding tool

- episodic-memory — Cross-session recall

- cc-log-viewer — Claude Code session viewer

Documentation:

See also: CLI AI Coding: A Vault of Valuable Things for a comprehensive list of repos, configs, and guidance.

Claude helped me write this post. A lot. But the thinking and tone are mine.